The Greedy Guide: Essential Problems and Solutions for Competitive Programming

Introduction

Hello everyone! 😄 Welcome back to my blog! Today, we're diving into the fascinating world of greedy algorithms in competitive programming. If you've ever wondered how to spot a problem screaming for a greedy solution or how to tackle those classic challenges that have left many scratching their heads, you're in the right place! Buckle up as we embark on this enlightening journey, breaking down these problems with detailed illustrations and explanations.

What is a Greedy algorithm?

A greedy algorithm builds a solution step-by-step, always selecting the option that seems best at that particular moment. This means it makes each choice without considering the broader context or reconsidering previous choices. Because of this inherent 'short-sightedness', greedy algorithms can be incredibly efficient but they might not always yield the correct result. It's intriguing to note that a single problem might present various paths for a greedy solution, yet typically only one of these paths is the true solution. Moreover, even if we stumble upon an approach that seems to work perfectly, proving its correctness across all scenarios can be a challenge, given the algorithm's fundamental greedy nature.

How to start thinking greedy?

Starting with greedy algorithms can make you wonder:

How do I know when to use a greedy approach? And How can I be sure my solution is right?

It might feel tricky at first. But here's some good news: There are many classic problems with clear greedy solutions. By studying these problems and understanding how they're solved, you'll slowly get better at spotting when to use a greedy method and how to apply it to new challenges.

Coin Problem

Imagine that you have an infinite supply of coins with values = {1, 2, 5, 10, 50, 100, 200} Now, someone gives you a number, let's call it N. The challenge? Figure out the fewest coins you'd need to make the exact amount of N.

Sounds fun, right? This problem is a classic one, and many find it a good starting point. The trick? Always choose the biggest coin that's not more than N. Once you've picked it, take it away from N, and keep going until you reach 0. Now, you might wonder, does this method always work? Well, for the coins that match our everyday money, the answer is yes!

Here's why our greedy coin-picking method works:

Using Bigger Coins: With coins like 1, 5, 10, 50, and 100, you'll never need more than one of each to get the best solution. Why? Well, if you tried to use two of the same coin (like two 5s), you could simply swap them out for a bigger coin (a 10) and end up with fewer coins.

A Limit on Some Coins: For coins like 2 and 20, you won't need more than two of them. Three 2s can be swapped out for a 5 and a 1. Similarly, three 20s can be changed for a 50 and a 10. So, you see, there's a better way!

Avoiding Inefficient Mixes: You also won't need combinations like 2 + 2 + 1 or 20 + 20 + 10 because you can just use a 5 or a 50 coin instead.

Best Way with Bigger Coins: For any bigger coin, you can't make its value using only smaller coins without needing more of them. For instance, the closest you can get to 100 using smaller coins is 99 (with coins 50, 20, 20, 5, 2, and 2). So, the greedy method of always picking the biggest coin really is the best way.

This example shows that it can be difficult to argue that a greedy algorithm works, even if the algorithm itself is simple.

Wrong Answer Scenario

I want to reiterate the fact that this solution always works for coins 1,2,5,10,50, and 100 that follow our monetary system. HOWEVER, in a general case where the set of coins can contain random values like coins = {1,3,4} and N = 6, this algorithm is going to produce the solution 4 + 1 + 1 which is incorrect, since the most optimal solution is 3 + 3. For such a problem with random coin values, we would have to implement a totally different solution using DP (Dynamic Programming)

Greedy Solution Code Implementation

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int n; cin >> n;

int coins[7] = {1,2,5,10,50,100,200};

int current = 6, coinsUsed = 0;

while(n){

if(coins[current] > n){current--; continue;}

n -= coins[current];

coinsUsed++;

}

cout << coinsUsed;

}

Time Complexity

The inner operations of the loop are O(1). The loop itself is O(n) in the worst case (but keep in mind that for many values of n, it will run far fewer iterations than n). Still, the overall time complexity is O(n).

Studying Algorithms Problem

Here is another very easy problem to warm up.

Steph wants to improve her knowledge of algorithms over winter break. She has a total of X (1 ≤ X ≤ 10^4 ) minutes to dedicate to learning algorithms. There are N (1 ≤ N ≤ 100) algorithms, and each one of them requires ai (1 ≤ ai ≤ 100) minutes to learn. Find the maximum number of algorithms she can learn.

Example:

N = 6, X = 15

a = {4, 3, 8, 4, 7, 3}

Result = 4

This problem is very nice since you can trust your intuition and decide to always try to do the tasks that require less time because logically it leaves more time available for the next tasks therefore maximizing the number of tasks done.

Code Implementation

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int n, x; cin >> n >> x;

vector<int>arr(n); for(auto &e:arr)cin >> e;

sort(arr.begin(), arr.end());

int sum = 0, res = 0;

for(auto e:arr){

if(sum + e > x)break;

sum += e;

res++;

}

cout << res;

}

Time Complexity

The most time-consuming operation is sorting, which has a time complexity of O(n log n). The other operations are linear (O(n)) or constant (O(1)).

So, in simple terms, the time complexity of the code is O(n log n).

Live Saving Boats Problem

Picture this: A cruise trip has gone horribly wrong, and passengers are in dire need of rescue. As part of the rescue team, your challenge is to determine the fewest number of life-saving boats needed to save everyone. However, there's a catch. Each boat can hold a maximum of two people and has a weight capacity of X (where 1 ≤ X ≤ 30,000).

Here's how the input is structured:

The first line provides an integer, X, indicating the boat's maximum weight capacity.

The next line offers an integer, N (where 1 ≤ N ≤ 50,000), representing the number of passengers awaiting rescue.

This is followed by N integers specifying the weight of each individual passenger. Note that each weight, Wi, will satisfy 1 ≤ Wi ≤ X.

Example

For X=100 and N=4 with weights:

W = {100, 60, 60, 40}

The solution is 3 boats. The most efficient arrangement is:

{100} - Only this boat can carry a person weighing 100. {60, 40} - Together, these two don't exceed the boat's limit. {60} - The remaining passenger.

Remember, in real-life scenarios, efficient problem-solving can make a world of difference!

To solve this problem we need to be very observant, I initially thought of iterating the weights, and for each Wi try to find the pair that would take you closest to the limit X as possible without exceeding. With this idea in mind, I made a key observation to solve this problem by looking at the persons with the greatest weight. I noticed how they were often too heavy to make any pair at all, taking a whole boat to themselves and if they could form a pair it would always be the most convenient to pair them with the lightest person. This is of course very greedy and I wasn't sure if it would work but the concept appeared to give the correct result for the example test cases.

Code Implementation

The solution approach that I decided to take was to sort the weights and use two pointers, one at the beginning pointing to the lightest person and one at the end pointing at the person with the most weight. While the pointers are separated, we try to pair the lightest with the heaviest, if it's not possible we simply send the heaviest person alone. Here is my code implementation for better understanding:

int x, n; cin >> x >> n;

vector<int>weights(n);

for(auto &e:weights)cin >> e;

sort(weights.begin(), weights.end()); // IMPORTANT

int boatsUsed = 0, lightest = 0, heaviest = n-1;

while(lightest <= heaviest){

if(lightest == heaviest){ // necesary to avoid summing twice for the following if

boatsUsed++;

break;

}

if(weights[heaviest] + weights[lightest] > x){ // case for when it's imposible to form a pair

boatsUsed++;

heaviest--;

}else{ // ideal case for when it's possible to form a pair.

boatsUsed++;

lightest++;

heaviest--;

}

}

cout << boatsUsed;

Notice how we don't have to actually save the pairs or modify the array for the algorithm to work.

Time Complexity

The code consists of:

Reading input: O(n)

Sorting weights: O(nlogn)

A while loop processing each passenger: O(n) worst case scenario for when all elements are too heavy and need a boat for each passenger.

The dominant factor is the sorting step. Hence, the overall time complexity is O(nlogn).

Now let's convince ourselves that our greedy solution works by asking ourselves the following questions:

Why start with the heaviest? If the heaviest person doesn't fit with the lightest, they won't fit with anyone else, because all other people are heavier than the lightest. So in this case, the heaviest person takes a boat alone.

Why pair the heaviest with the lightest? By trying to pair the heaviest and the lightest, we aim to use the remaining space on the boat after the heaviest person efficiently. If they fit together, that's the most people we can fit on that boat (because it's only allowed two). If they don't, we already know the heaviest person should go alone.

As you can tell once again, it's hard to prove that the solution is correct before submitting it but for this particular problem this solution actually outputs the most optimal and correct answer for all cases.

The Scheduling Problem

Many problems that involve efficient usage of time can often be solved with a greedy approach, a great example of the very classic "Scheduling" problem.

There are N events (1 <= N <= 1e6). Each event is described by its starting and ending times (0 <= S < E <= 1e9). You want to attend the maximum amount of events possible, you can only attend one at a time, and if you choose to attend an event you have to attend the entire event from beginning to end. Traveling between events is instantaneous.

What is the maximum number of events you can assist?

Examples

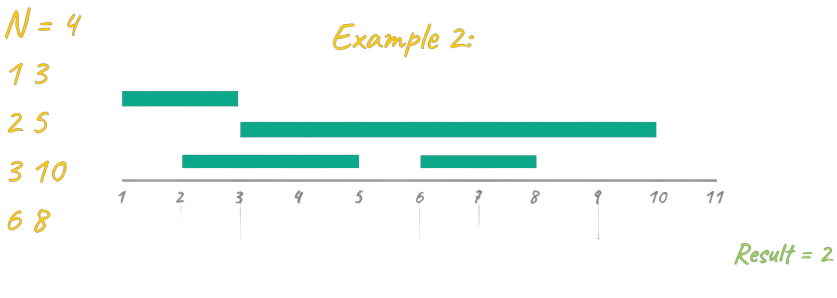

In the case above you can assist events {2-4} {5-6} {7-10} which it's the maximum amount possible, if you try to assist event {1-9} you are unable to attend any other.

In example 2 there are 3 combinations that give the maximum result of 2, you can assist events {1-3} {6-8}, {1-3}{3-10}, or {2-5}{6-8}.

In this last example, we have more events and several solutions that have a maximum result of 4. An example of an optimal solution is: {1-4}{4-5}{5-8}{8-9}.

Solution Breakdown

When I was first tasked with this problem, I immediately thought of analyzing the example cases by drawing the timeline in order to understand the relationship between the input and the correct result. By drawing the events on paper the result became easily apparent on sight. Physically drawing the events is an excellent idea for this problem in particular because when trying to draw them you are going to question if it's convenient to have them in a special order. Having the events ordered means that you can iterate the events and worry about comparing only two at a time.

Algorithm 1 - "Earliest Starting Event"

In this first approach, we want to sort all the events by starting point. This means always selecting the next possible event that begins as early as possible. Let's visualize all of the examples after applying this sort.

In the animation above you can see the algorithm in action for example 2. Observe how the first event is always chosen and from there, for each event you ask if it's overlapping with the last chosen event, if it is overlapping, you ignore it and continue. else you mark it as chosen. For example 2, this algorithm prints the correct result of 2, However, before concluding that this algorithm works you should first test it again with the other test examples.

Amazingly this algorithm outputs 4 which is the correct result for this case as well.

Let's try to simulate the algorithm one last time for example 1.

This example is a very simple base case and it's clear how this algorithm breaks and no longer outputs the correct result. Looking at this example is enough to discard this sorting idea.

Algorithm 2 - "Duration"

Once algorithm 1 was proven to be incorrect I cleared my mind and decided to think about all the previous greedy problems, remembering the problem "Studying Algorithms", As we saw previously, the solution to that problem was to always pick the tasks that required the less time because it logically allowed more time to complete other tasks.

With that idea in mind, I decided to try the previous algorithm for all example test cases but with the events sorted by duration.

As seen in the animation above this approach gives the correct result for example 1

In Example 2 however, the result is clearly incorrect, outputing 3 instead of 2. By visualizing this case in action it's very clear that this idea is not going to work, since, unlike the "learning algorithms" problem there are starting and ending points that must be taken into account. Another thing that you can look at is the fact that if you have a "group" of events and then you have a second separated group, you must make sure they don't mix during the processing. Example:

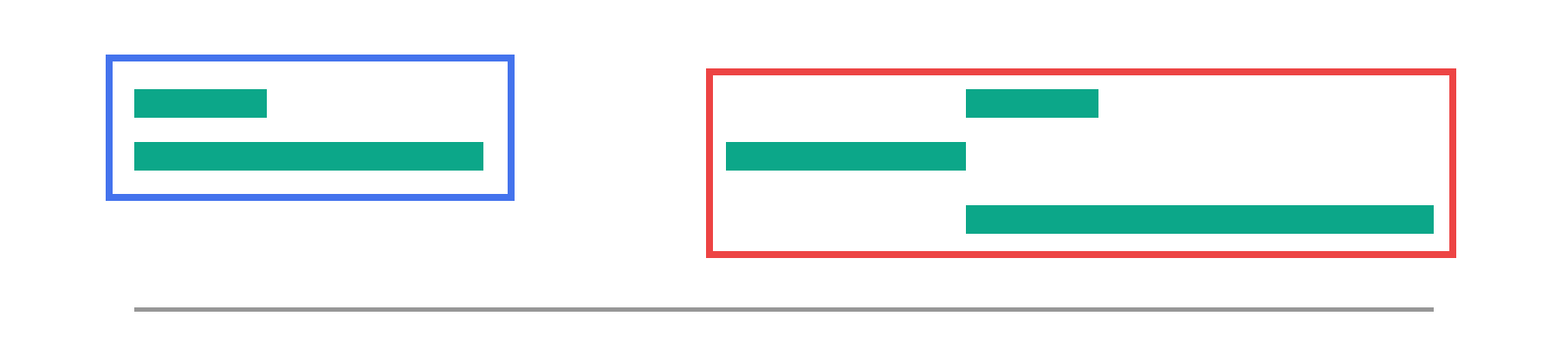

With the illustration above you can see that the logically correct thing do to is process the events in the blue group and in a separate manner process the events that are in the red group, however, this algorithm mixes them all up.

Algorithm 3 - "Earliest Ending Event"

The correct greedy approach for solving this problem is to sort the events by ending times, the logic behind this idea is that the sooner an event ends the more opportunity you have to test with more events that come after.

Let's visualize this approach in action for all the test cases.

As you can see from all of the animations above, this code outputs the correct result for all test cases.

Code Implementation

struct ev{

int start, end;

bool operator < (const ev &b)const{return end < b.end;} // sort by end

};

bool notOverlap(ev a, ev b){

return (b.start >= a.end && b.end > a.end) || (b.end <= a.start && b.start < a.start);

}

int main() {

int n; cin >> n;

vector<ev> events(n);

for(auto &e:events)cin >> e.start >> e.end;

sort(events.begin(), events.end());

if(events.size() == 1){cout << 1; return 0;}

ev lastValid = events[0];

int res = 1;

for(int i=1;i<n; i++){

if(notOverlap(lastValid, events[i])){

lastValid = events[i];

res++;

}

}

cout << res;

}

Notice how the events are nicely represented by a custom-made struct called "ev" that has the starting and ending times represented by integers. Notice how in that same struct we define an operator that is needed to easily sort the events by end time using the sort() procedure. The rest is really straightforward, we iterate the events array and if the last valid event and the current event do not overlap, then we set the new last valid event and increment the answer.

Time Complexity

The code consists of:

Reading input: O(n)

Sorting the events: O(nlogn)

A for loop that processes each event: O(n)

The dominant factor is the sorting step. Hence, the overall time complexity is O(nlogn).

Flipping Consecutive Coins Problem

You have N (1 <= N <= 1000) coins in a row, each showing either "1" or "0". In a single move, you can choose any K (1 <= K <= 1000) consecutive coins and flip them to their opposite side (e.g., "0" becomes "1" and vice versa).

Your task: Determine the minimum number of moves required to make all coins display "1". If it's impossible to achieve this, output "-1".

Example

Input:

5 2

1 0 1 0 1

Output:

2

In this example there are 5 coins and K = 2, this means that you can pick any 2 consecutive coins and perform a flip, Note that you have to pick exactly 2 elements not less. for this specific initial coin layout, you can perform a flip in the range [1, 2] (zero-indexed) leaving the coins as: 1 1 0 0 1 and then do a flip in the range [2, 3] resulting in 1 1 1 1 1, in only 2 moves, which is the minimum amount possible.

BFS Approach

When I first came across this problem I looked at three important points.

The fact that N and K could have a worst case of 1000 which is a relatively small limit.

The fact that you were asked to figure out a minimum distance to state "11111..."

The statement specifies to print -1 if there is no solution.

All of the points above are very classic observations for problems that can be solved using a BFS/DFS approach which I immediately tried to implement without thinking of another more simple approach.

If you have never heard of BFS or DFS I strongly advise you to read my BFS and DFS Beginners Overview in order to understand the solution approach for this problem. However, as we'll see later on, this solution gives an MLE (Memory Limit Exeded) verdict so feel free to skip this section.

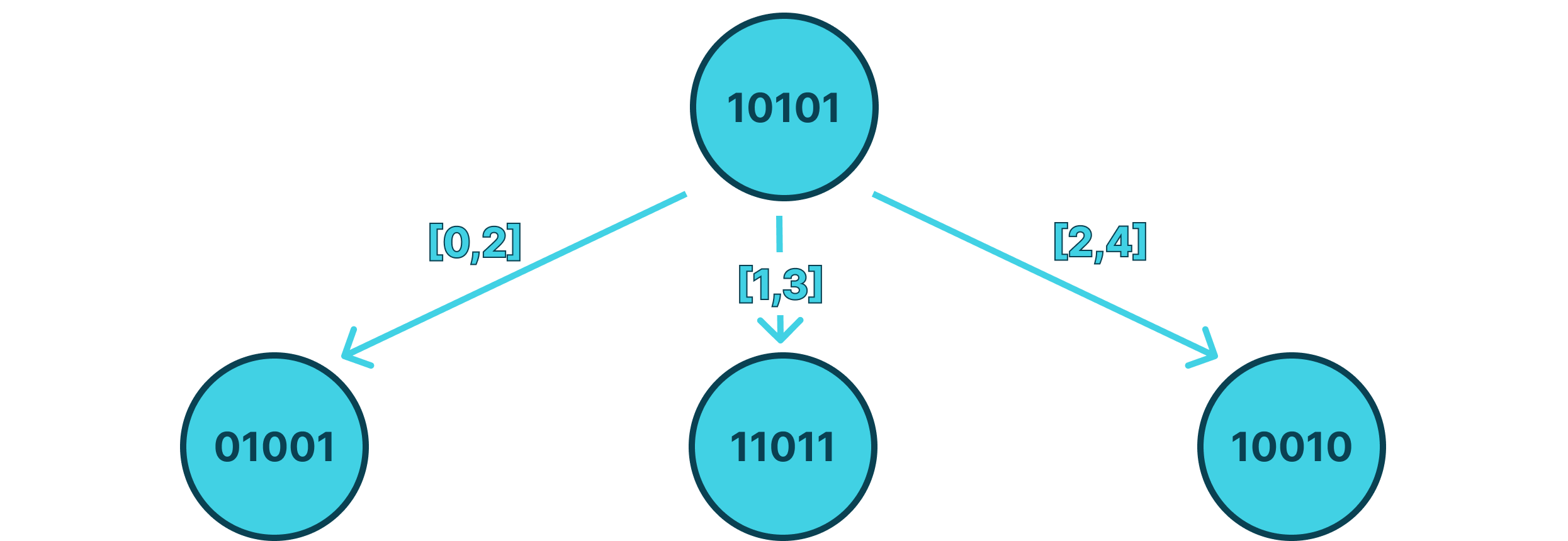

The way I managed to implement this solution was to visualize the way to represent a node, in this case, I figured that I could represent a coin configuration 1 0 1 0 1 as a string with no spaces "10101". With this, you can create an Adjacency list but with an unordered_map<string, int>. You can also represent the desired "final" node as string "11111". Lastly, the BFS algorithm logic remains the same, in which for a node, you visit the adjacent nodes and mark them as visited to avoid repeating, and by doing this you can test all possible Paths (simulate the flips) in an efficient manner, for example:

In the image above you can see that for the initial node 10101, you have 3 adjacent nodes which are the resulting states after performing the flips in ranges: [0,2], [1,3], [2,4]. the initial node always has a distance of 0 flips but for this particular problem, I decided to set it to 1 and then subtract 1 to the answer at the end, the reason being that we need 0 to represent not visited, traditionaly we used -1, but since we are working with a sting map we can't use that. The adjacent nodes are going to have a distance of the parent + 1, this way, if we get state 01001 later on we can trim that search since we know it was visited in a more optimal manner before.

unordered_map<string, int> dist; // Adjacency List

int main() {

std::cin.tie(nullptr);

std::ios_base::sync_with_stdio(false);

int n, m; cin >> n >> m;

string initial = ""; // representing the coins as a string with no spaces

for(int i=0; i<n; i++){

char x; cin >> x;

initial += x;

}

queue<string> BFS;

BFS.push(initial); // starting BFS

dist[initial] = 1; // starting from 1 because we need 0 to represent not visited

while(BFS.size()){

string c = BFS.front(); // getting current node

BFS.pop();

for(int i=0; i<=n-m; i++){ // create all possible adjacent nodes

string adj = "";

for(int j=0; j<i; j++)adj += c[j];

for(int j=i; j<i+m; j++)adj += c[j] == '1'?'0':'1';

for(int j=i+m; j<n; j++)adj += c[j];

// add node to BFS if not visited.

if(dist[adj] == 0){BFS.push(adj); dist[adj] = dist[c] + 1;}

}

}

string endNode(n, '1'); // create ending node

if(dist[endNode] == 0)cout << -1; // no answer case

else cout << dist[endNode]-1; // print the minimum distance to the ending node

return 0;

}

Time and Space Complexity Analisis

Unfortunately, this solution is not the most optimal possible and gives a MLE verdict. Let's see why:

You're flipping K consecutive coins in a sequence of N coins, where (N = 1000). Let's consider the worst-case scenario for the number of combinations, i.e., the number of unique sequences you could generate by flipping any K consecutive coins.

For a given starting position

i, there's only one unique sequence after flippingKconsecutive coins.You can start flipping from position

i = 0toi = N-K. This means there are (N-K+1) possible starting positions for flipping.So, for each starting position, you get a new sequence. In the worst case, every single one of these could be unique, leading to (N-K+1) unique sequences.

However, note that this is just the number of unique sequences obtained from a single flip. When you consider multiple flips, the number of unique sequences can increase dramatically as you can flip any possible segment of K coins in any of these sequences.

So, you can think of it like this:

From the initial state, you have (N-K+1) sequences. From each of those, you can have up to (N-K+1) more sequences and this can keep going.

Now, not every sequence will be unique. Some flips will revert a previous flip, and others might lead to a sequence you've already seen. But even considering that, it's clear that the potential number of combinations can explode quickly, especially as the number of flips (and hence the depth of the BFS) increases.

This doesn't even get us to an exact number, but you can already see how the combinations can quickly grow into the thousands or even millions, which can easily exceed memory limits. Thankfully, this solution is enough to get a partial result, but we'll see in the next section how to get a 100% score.

Greedy Approach

In order to spot this solution you need to think about the fact that you want all zeros to become 1, and once a value becomes 1 you don't want to modify it under any condition.

With this idea in mind, you can simply iterate the coin array, and if you find a 0 you HAVE to flip the range starting inclusively from that position to that position + k, repeating the process until you finish iterating the array or until you are forced to perform an impossible flip, this means that there are not enough coins for a flip to happen, for example, 1110. Notice how you would get a segmentation fault error.

Basically, this approach works because once we perform a flip we never look back and we will never under any condition flip a previously flipped 0 coin again meaning that it's guaranteed to be the most optimal answer possible.

Here is my code implementation:

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int n, m, res = 0; cin >> n >> m;

vector<int>arr(n); for(auto &e:arr)cin >> e;

for(int i=0; i<=n-m; i++){

if(arr[i] == 0){

res++;

for(int j=i; j < i+m; j++)arr[j] = arr[j] == 0?1:0;

}

}

bool valid = true;

for(auto e:arr)if(e == 0)valid = false;

cout << (valid?res:-1);

return 0;

}

Notice how the handling for the impossible case is very easy to check, we just iterate the array after performing the algorithm, and if there is any 0 left, it's imposible and we should output -1, else we just print the res variable that counted the amount of flips.

Time and Space Complexity

Reading the input: O(n) - Because you're reading 'n' numbers into the arr vector.

Main Loop: O(n×m) - The outer loop runs 'n' times, and for each of those, the inner loop runs 'm' times (in the worst case). So, together, it's like multiplying 'n' and 'm'.

Checking the result: O(n) - You're going through the arr vector again to see if all coins show "1".

Combine all these, and the time complexity is O(n+n×m+n), which simplifies to O(n×m).

For the Space complexity, we have the Vector: O(n) - The arr vector stores 'n' numbers and Other Variables: These just take up constant space. No matter how big 'n' or 'm' get, the space used by variables like n, m, res, and valid doesn't grow.

So, the space complexity is O(n). Giving us an AC verdict with a much simpler solution. 🥳

Interval Flipped Coin Problem

You have an endless row of coins, all initially showing heads. And you are given N inclusive range intervals. Write a program that outputs the fewest number of coins you need to flip to ensure there's at least one tails in each of the M intervals provided to you. (heads is represented by '0' and tails by '1')

Example

input:

3

1 6

2 9

1 4

output:

1

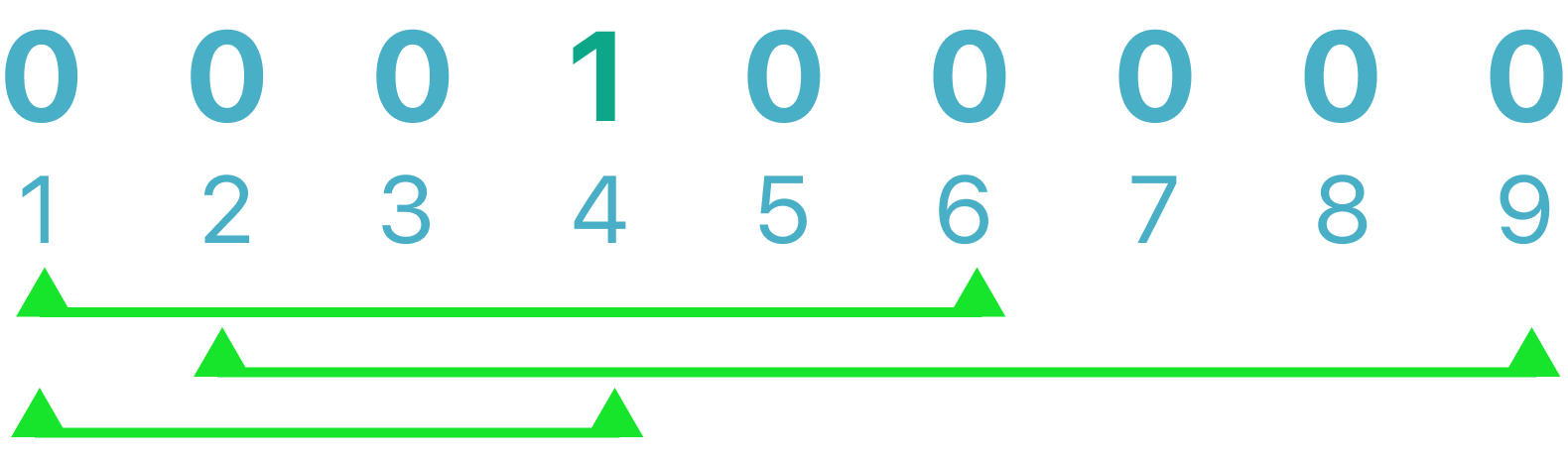

In this example you are given 3 inclusive intervals, by drawing them, the solution becomes clear, you only need to flip 1 coin, which is the minimum amount of flips for a valid solution, in the image I flipped coin 4, however, flipping the coin 3 or 2 are also valid answers. For this problem, you don't need to print the positions of the flipped coins, only the amount.

Limits

1 <= N <= 100,000

1 <= i <= j <= 1,000,000 in which i represents the starting index and j represents the ending index to the inclusive interval.

Solution Breakdown

Amazingly this problem has an almost exact solution to The Scheduling Problem in which we sort all intervals by end-time.

The algorithm would work as follows:

Sort the intervals by end time

Keep track of the position of the last 1/flip (initially there is none so it can be initialized with -1)

Iterate the Intervals and for each one ask if the starting point is less than the position of the last 1/flip, if true it means that the last one/flip is still within the current interval and there is no need to make any flip. If false, it means that are forced to make a flip, we choose to follow a greedy strategy by doing the flip at the end position of that interval because it is the most efficient place to target the following intervals.

Code Implementation

struct range{

int i, j;

bool operator < (const range &b)const{

return j < b.j;

}

};

int main() {

int n; cin >> n;

vector<range> arr(n);

for(auto &e:arr)cin >> e.i >> e.j;

sort(arr.begin(), arr.end());

int lastFlip = -1, res = 0;

for(auto e:arr){

if(e.i > lastFlip){

res++;

lastFlip = e.j;

}

}

cout << res;

return 0;

}

As you can see the solution is incredibly simple, yet it gives us the correct output every time in the most efficient way possible.

Time and Space Complexity

The code consists of:

Reading input: O(n)

Sorting the intervals: O(nlogn)

A for loop that processes each interval: O(n)

The dominant factor is the sorting step. Hence, the overall time complexity is O(nlogn).

For the space complexity, we only have to store the M intervals in an array, resulting in a space complexity of O(n).

Conclusion - Farewell

We've journeyed through the exciting world of greedy algorithms together, learning how to spot problems that call for a greedy solution, and breaking down some classic examples. Our adventure into the code, along with its time and space analysis, hopefully gave you a clearer understanding and maybe sparked your curiosity a bit.

With each problem, we saw how a simple idea can lead to solutions that are both smart and efficient. We also noticed how the right approach can help find the best solutions, and how different coding choices can affect how fast our code runs and how much memory it uses.

Feel free to share this post with others who might be interested in diving into greedy algorithms, and don’t hesitate to drop your thoughts or questions in the comments below. Your interactions make this community a fun and enriching place to learn. Until next time, happy coding! 💻