Hello everyone 👋, welcome back to another article, today are going to dive into a very cool graph algorithm called "Tarjan", we are going to see what it is, how it works, what it's used for, and we are going to upsolve two very cool competitive programming problems that are solved using this algorithm.

If you haven't heard of Graphs, or have very little knowledge in this subject. I strongly advise you to read my posts:

What is the Tarjan Algorithm?

Tarjan's Algorithm is a classic solution in competitive programming used to find strongly connected components in a directed graph. A strongly connected component is a group of nodes where you can travel from any node to any other node in the group and find a way back. You can kind of see a strongly connected component as an island of nodes in a graph that forms a loop.

How does Tarjan Work?

This algorithm is extremely similar to the DFS algorithm, I personally love the recursive implementation of this algorithm that works as follows:

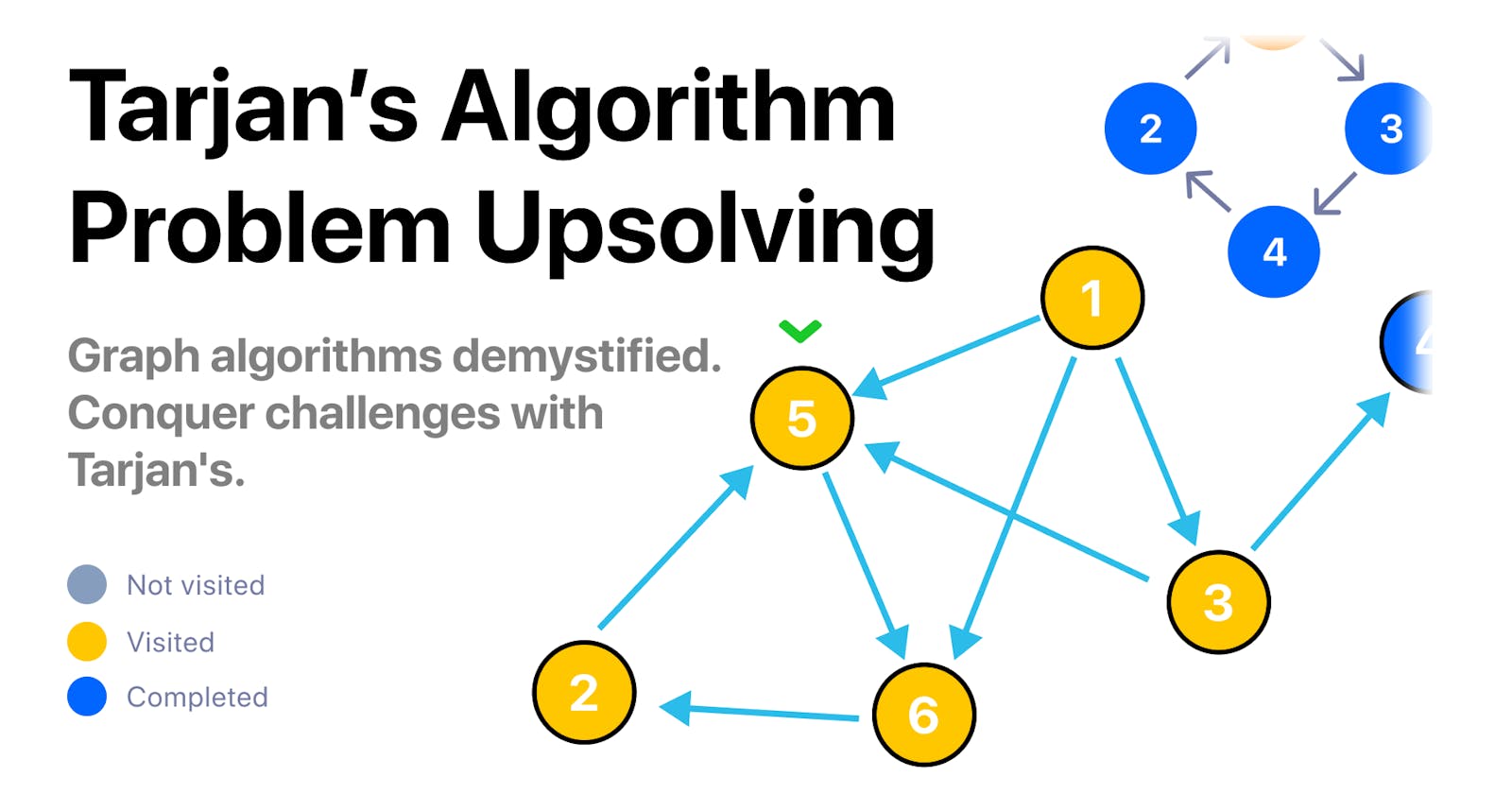

Initialize a "state" vector, this will replace the "visited" vector on the classic DFS algorithm, it works very similarly, the big difference is that the visited vector is made out of booleans since you only have two states for a node: visited, and not visited. However, now with our state vector, we have 3 states for a node: 0, 1, and 2, where 0 represents not visited, 1 represents visited, and 2 represents completed.

For each node that is not completed, send the tarjan function through that node.

On every Tarjan function call, this procedure is going to mark the current node as visited/1, visit all adjacent nodes to the node, and if you find that one of them has a state of 1, it means that a loop exists, in which case you must end the recursion and output that a loop exists in the graph, if the adjacent node has a state of 2, it means that it has been completed before and you can simply ignore it. if an adjacent node has a state of 0 then you must send the Tarjan algorithm through that unvisited node, repeating the process until there are no more unvisited adjacent nodes. When that happens, you mark the node as completed.

This sounds a bit confusing with text, let's visualize the algorithm in action.

In this first animation, we can see how the algorithm successfully traverses the graph without encountering a cycle, this means that this graph is a valid DAG (Directed Acyclic Graph). Now let's change the graph just a little bit, let's flip the direction of the edge connecting nodes 2 and 6 and run the algorithm again.

Tarjan Code Implementation

There are several ways to implement this algorithm, below I showcase my personal choice, which uses an adjacency list to represent the graph, recursion, and it's the most simple in my opinion.

// Data structure to represent the graph. Each node is represented by an integer,

// and graph[node] is a vector of the nodes to which node has an outgoing edge.

vector<vector<int>> graph;

// The state of each node in the graph during the traversal:

// 0 = not visited, 1 = visited, 2 = completed.

vector<int> state;

bool tarjan(int node){

state[node] = 1; // Mark the node as visited

for(auto adj : graph[node]){ // Iterate through all nodes adjacent to the current node.

if(state[adj] == 2) continue; // Skip nodes that are already completed.

if(state[adj] == 1) return true; // A cycle is detected if an adjacent node is visited but not yet finished.

if(tarjan(adj)) return true; // Recur for adjacent nodes, and return true if any of those recursions detect a cycle.

}

state[node] = 2; // Mark the node as finished.

return false; // No cycle was detected from this node.

}

int main() {

int n, m; cin >> n >> m; // Read the number of nodes and edges.

graph.resize(n+1); // Resize the graph to have n+1 elements (nodes are numbered from 1 to n).

state.resize(n+1, 0); // Resize the state vector and initialize all states to 0 (not yet visited).

for(int i = 0; i < m; i++){ // Read the edges of the graph from standard input.

int a, b; cin >> a >> b;

graph[a].push_back(b); // Add an edge from node a to node b.

}

bool cycleFound = false;

for(int node = 1; node <= n; node++){ // Check each node for cycles.

if(state[node] != 2){ // Skip nodes that are already finished.

if(tarjan(node)) cycleFound = true; // If a cycle is detected from this node, set cycleFound to true.

}

}

// Output whether or not a cycle was detected.

cout << (cycleFound ? "There is a cycle in this graph" : "valid DAG graph :D");

}

What is the algorithm used for?

In competitive programming, Tarjan's Algorithm is essential for solving problems related to network connectivity and finding cycles in graphs, more concisely, this algorithm is mainly used to check if a graph is a valid DAG graph (Directed Acyclic Graph) this is a directed graph that does not contain loops. Being able to identify strongly connected components efficiently is often the key to optimizing your solutions and excelling in competitions.

Enough talk for now, let's understand this better by solving two very cool competitive programming challenges using this algorithm.

Catching the Criminals Problem

There is a city represented by a rectangular grid of N x M squares (1 <= N, M <= 1000), unfortunately for this city, there is a gang of criminals that wants to take control of the streets and are not planning on leaving, thankfully, the local police have developed an amazing trap that can cover an entire square of the city grid, if any gang member lands on one of those squares it is guaranteed that he will be captured. The police chief of this city has asked for your help in developing an algorithm that outputs the minimum amount of traps needed to eventually catch the entire gang. To do so, he has valuable information for you. After countless hours of analyzing each individual square of the city, they have figured out that the gang has a fixed direction to go after for each square.

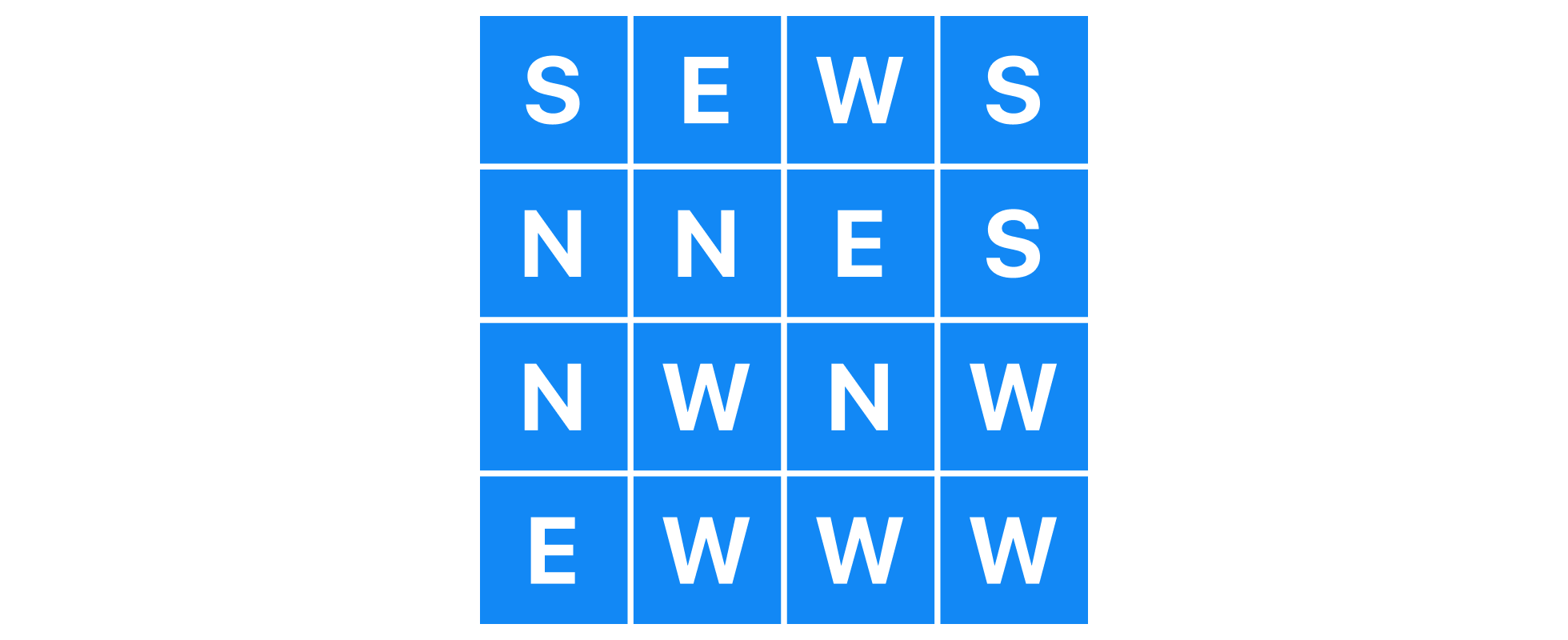

Example:

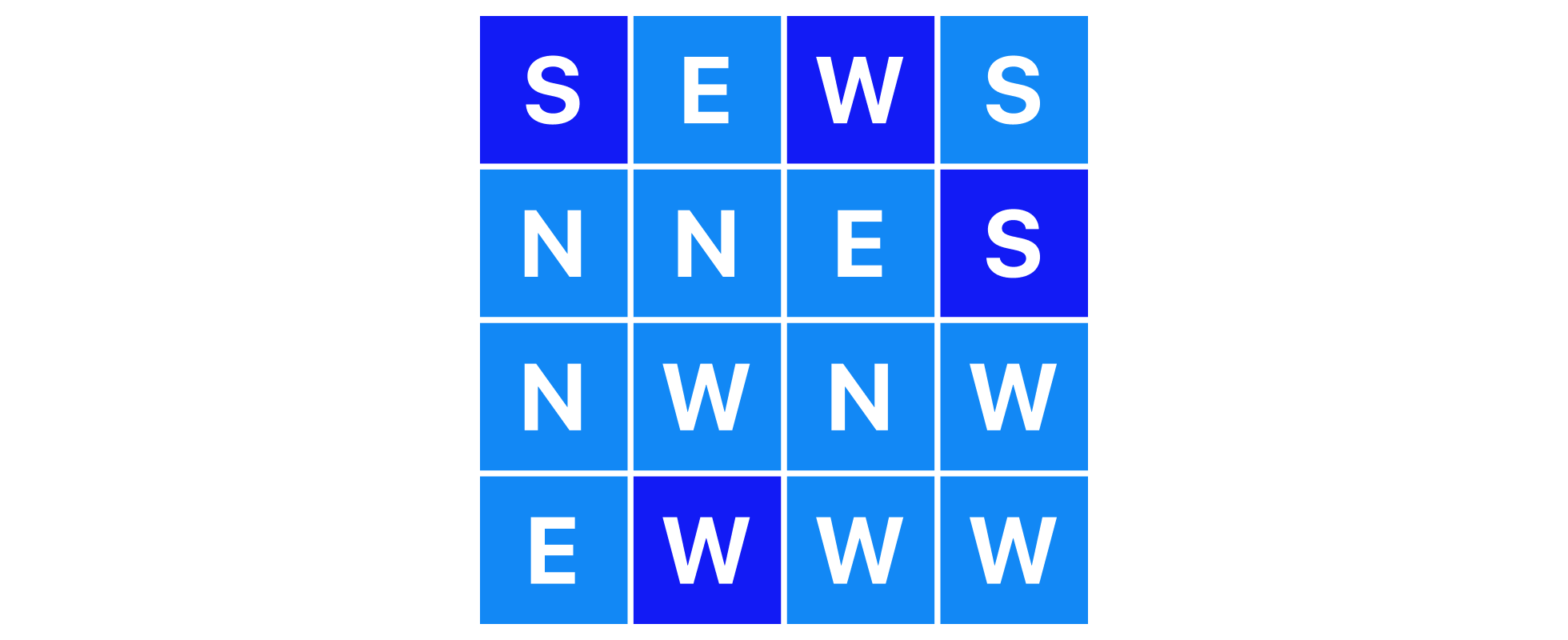

The matrix above is an example of the information given to you, it means that for square {0,0} it is guaranteed that if a criminal lands on that square, he is going to head to the South, square {1,0} next.

S = South

N = North

E = East

W = West

It's guaranteed that the information will always be valid, you can be certain that no square is going to point outside the city.

For the Example shown above the answer should be 4.

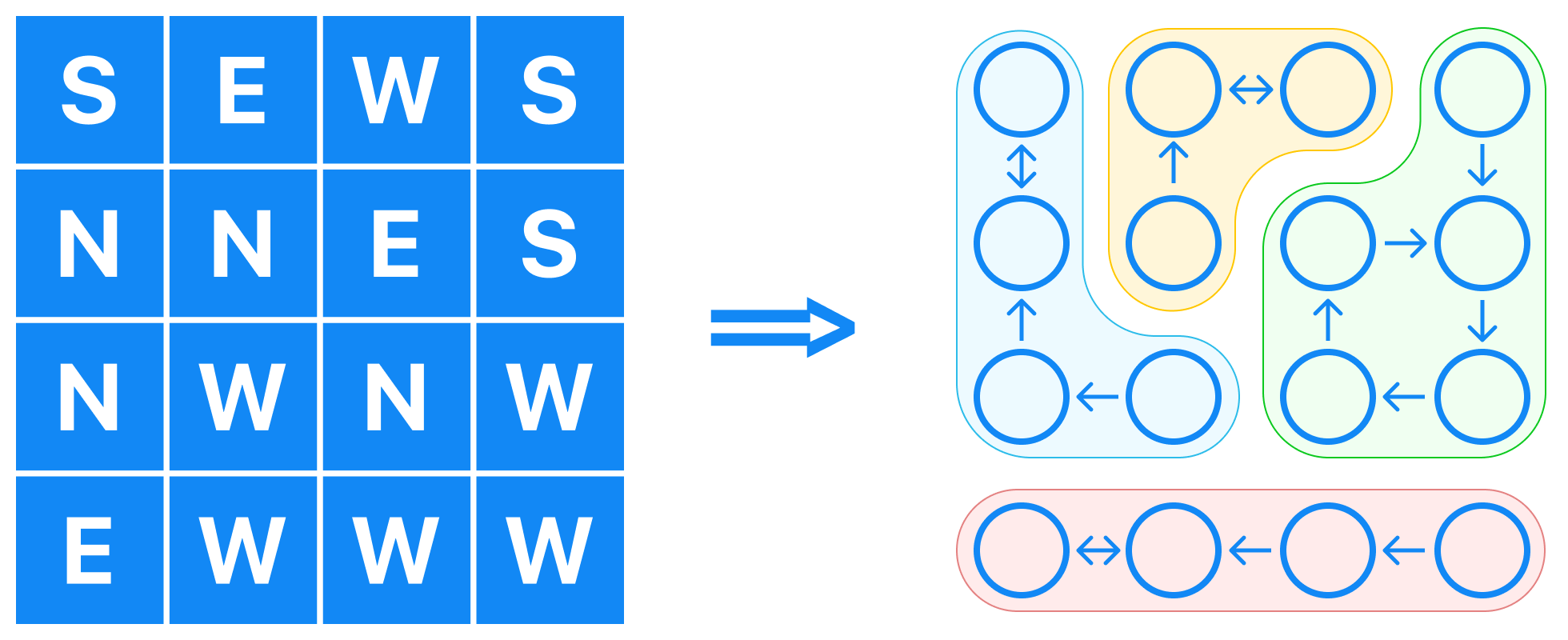

Above is one correct layout for the traps, I encourage you to pretend there is a criminal in each cell and follow the "path" for each one in order to visualize how they eventually end up in one of the traps. There are several correct layouts for this example, however, the minimum amount needed is 4. Remember that you don't need to output the configuration of the traps, just the minimum amount.

Solution Breakdown

This problem looks very intimidating and just by looking at the problem you might think that the solution is very complex. However, that is not the case, the key to solving this problem is to look at the example map as an explicit graph first.

Once you grab a piece of paper and draw the explicit graph for the provided example you can clearly see how we have a directed graph and the answer is simply the amount of strongly connected components, or "islands" in the graph. Since we have possible cycles we have to use Tarjan's algorithm.

Code Implementation

// Defining arrays to store the city grid and visited status of each square

char map[1005][1005]; // Stores the direction in which the gang will move from each square

int v[1005][1005]; // Visited status: 0 (not visited), 1 (visited), 2 (fully processed)

int res = 0; // Result variable to store the total number of traps required

// Tarjan's algorithm function to process each square in a depth-first manner

void tarjan(int i, int j){

v[i][j] = 1; // Marking the current square as visited

int adji, adjj; // Variables to hold coordinates of the adjacent square

// Determining the coordinates of the adjacent square based on the direction

if(map[i][j] == 'N'){adji = i-1; adjj = j;}

if(map[i][j] == 'S'){adji = i+1; adjj = j;}

if(map[i][j] == 'E'){adji = i; adjj = j+1;}

if(map[i][j] == 'W'){adji = i; adjj = j-1;}

// If the adjacent square is visited but not processed, increment the trap count

if(v[adji][adjj] == 1)res++;

// If the adjacent square is unvisited, recursively apply Tarjan's algorithm

else if(v[adji][adjj] == 0)tarjan(adji, adjj);

v[i][j] = 2; // Marking the current square as fully processed

}

// Main function

int main(){

int n, m; // Variables to hold the dimensions of the city grid

cin >> n >> m; // Reading the dimensions from the input

// Reading the city grid from the input

for(int i=0; i<n; i++)

for(int j=0; j<m; j++)

cin >> map[i][j];

// Processing each square in the city grid

for(int i=0; i<n; i++){

for(int j=0; j<m; j++){

// If the square is unvisited, apply Tarjan's algorithm

if(v[i][j] == 0)tarjan(i, j);

}

}

cout << res; // Outputting the total number of traps required

return 0; // Returning 0 to indicate successful execution

}

Time and Space Complexity

Time Complexity:

Grid Reading: Reading the grid has a time complexity of (O(N * M)), where (N) is the number of rows and (M) is the number of columns.

Tarjan's Algorithm: Tarjan's algorithm here processes each square in the grid exactly once. Specifically, each square is marked visited once and fully processed once. The recursive depth-first nature of the algorithm ensures that no square is visited more than once. This results in a time complexity of (O(N * M)) for the traversal.

Considering both the grid reading and Tarjan's algorithm, the overall time complexity remains (O(N * M)).

Space Complexity:

map Array: The space used to store the direction in each grid square is (O(N * M)).

v Array: The space used to keep track of the visited status for each grid square is also (O(N * M)).

Recursive Stack: In the worst case, the depth of the recursive calls for the

tarjanfunction can be (O(N * M)) if all squares are connected in a linear sequence. This is rare, but for complexity analysis, we consider worst-case scenarios.

Adding up all the above, the total space complexity is (O(N * M) + O(N * M) + O(N * M)) which simplifies to (O(N * M)).

In conclusion, both the time and space complexities of the provided code are (O(N*M)).

Faulty Subway Doors Problem

Mexicos City metro is one of the largest in the world, unfortunately, the wagon that you just boarded has a faulty door system. The wagon has P doors numbered from 1 to P, and D of those doors are faulty. Each of the faulty doors is linked to a specified group of doors which it affects. When you try to close a faulty door, the group for that faulty door opens (this group can even contain the door that you just tried to close). Of course, normal doors close without affecting anything.

You are given Q queries, each query is going to specify which doors are initially open and you must output whether or not it's possible to close all doors with "YES" or "NO".

Example

for the following input:

3 2 2 // P, D, Q (amount of doors, amount of faulty doors, amount of queries)

2 1 1 // door 2 opens 1 door, door 1

1 1 2 // door 1 opens 1 door, door 2

1 3 // query, 1 door open, door 3

2 1 2 // query, 2 open doors 1 and 2

The output should be:

YES

NO

In the example we have P=3 (there are 3 doors), D=2 (2 doors are defective), and Q=2 (you will be asked 2 questions). When you close door 2, a door will open, which is number 1. When you close door 1, a door will open, which is number 2. In the first question, door 3 is open and the others are closed. Therefore, you only have to close door 3, since this one is not defective, no other doors will open and all doors can remain closed (the answer to that question is YES). In the second question, doors 1 and 2 are open and it is not possible to close one without opening the other (the answer to that question is NO).

Limits

1 <= P <=100000

The sum of all Di will not be greater than 1000000.

The sum of all Qi will not be greater than 1000000.

The Index of the doors will always be between 1 and P inclusive.

Solution Breakdown

Once again we can see a great example of a quite intimidating problem, however, a great key point to mention is the fact that you are not asked for the minimum amount of actions (closing doors), or to recreate the "path" of actions you had to do in order to close all doors, instead, you are only asked if it's possible to close them all given an initial configuration.

By observing and thinking about the problem, you can realize that no matter how many faulty doors open functional ones, it will always be possible to close all functional doors at the end. Because of this, you only have to look at faulty doors.

Faulty doors can always be closed as long as you don't enter a cycle. for Example:

See how in example 1 you can eventually close the open door 5, however, in example 2 eventually you fall into a cycle after trying to close door 5 making it impossible to close all doors. Example 3 does not contain any initially open doors, I added the case to emphasize that the cycles are not a problem as long as no open doors lead to one.

After analyzing this, we can rephrase the problem as:

Given a Directed Graph, output "NO" if an open door node leads to a cycle. else output "YES".

Immediately we must think of Tarjan's algorithm. My first solution involved sending Tarjan's algorithm from each open node of each query, however, given that the amount of queries is very large, this solution will give us a TLE (Time Limit Exceded) verdict.

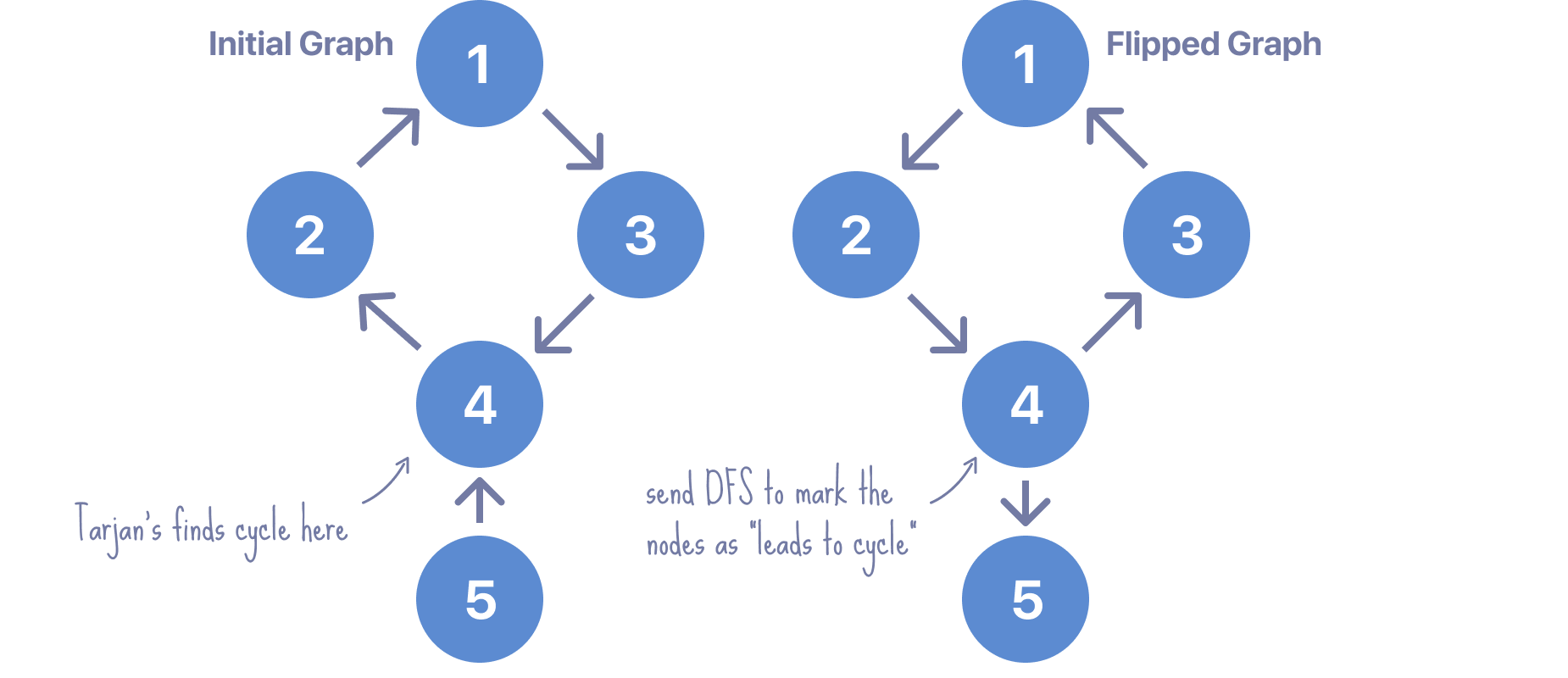

We can optimize the solution by running Tarjan's algorithm only once and in the case a cycle is found we can mark all the nodes that reached that cycle as "leads to cycle". The way we do this is by having a flipped graph like this:

We send a simple DFS algorithm from the node in which the cycle was found, marking all visited nodes by the DFS as nodes that lead to a cycle in a vector. This allows us to answer queries very simply by iterating through the open nodes and asking in constant time O(1) if they lead to a cycle.

Code Implementation

#include<bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

// Declare global variables for the number of doors, faulty doors, and queries

int p, d, q;

// Define a graph for door relations and its flipped version

vector<vector<int>>GRAPH;

vector<vector<int>>FlippedGraph;

// Vector to store the status of a node during tarjan's algorithm

vector<int> status; // 0 not visited, 1 visited, 2 ended.

// Vector to mark nodes that have been visited during DFS

vector<int>visited(1e5+5,0);

// Vector to mark nodes leading to a cycle

vector<bool>leadsToCycle;

// Depth First Search function

void dfs(int node){

leadsToCycle[node] = true;

visited[node] = true;

for(auto adj:FlippedGraph[node])if(!visited[adj])dfs(adj);

}

// Tarjan's algorithm to detect cycles

void tarjan(int node){

if(status[node] == 2)return;

if(status[node] == 1){

dfs(node);

}else{

status[node] = 1;

for(auto adj:GRAPH[node])tarjan(adj);

}

status[node] = 2;

}

int main(){

// Input number of doors, faulty doors, and queries

cin >> p >> d >> q;

// Resize the graphs and vectors based on the number of doors

GRAPH.resize(p+1);

FlippedGraph.resize(p+1);

status.resize(p+1);

leadsToCycle.resize(p+1, 0);

// Input relationships of faulty doors

while(d--){

int node, size; cin >> node >> size;

while(size--){

int adj; cin >> adj;

GRAPH[node].push_back(adj);

}

}

// Construct the flipped graph for relations

for(int node = 1; node <= p; node++) for(auto adj:GRAPH[node])FlippedGraph[adj].push_back(node);

// Check each door using tarjan's algorithm to find cycles

for(int node = 1; node <=p; node++){

if(status[node] == 0){

tarjan(node);

}

}

// Answer the queries

while(q--){

int n; cin >> n;

bool possible = true;

while(n--){

int x; cin >> x;

if(leadsToCycle[x])possible = false;

}

cout << (possible?"S":"N") << "\n"; // Output "S" for yes, "N" for no

}

return 0;

}

Time and Space Complexity Analysis

Reading the number of doors, faulty doors, and queries takes constant time, O(1).

Inputting relationships of faulty doors: This operation is bounded by the number of faulty doors and the number of affected doors. In the worst case, every door affects every other door, which would take O(P^2) time. But typically, this is a lot less than that in practice.

Constructing the flipped graph: This is a nested loop, iterating through each door and its associated doors. Again, this can go up to O(P^2) in the worst case.

Tarjan's algorithm for cycle detection: In essence, Tarjan's SCC (Strongly Connected Components) algorithm runs in linear time with respect to the number of nodes and edges, O(P + E), where E is the number of edges (or door-door relations in our context).

Answering the queries: For each query, in the worst case, we check every door. This takes O(P*Q) time for all queries.

Combining the above, our total time complexity is roughly O(P^2 + P + E + PQ).

2. Space Complexity:

Storing the

GRAPHandFlippedGraph: Since both of these graphs store relationships between doors, they can take up to O(P^2) space in the worst case.Auxiliary vectors (

status,visited,leadsToCycle): All these vectors have a length of P, giving O(P) space for each, so O(3P) in total.Temporary variables in the main function and recursive calls stack space are also considered, but they won't exceed the above complexities.

Therefore, our total space complexity is roughly O(P^2 + 3P).

In Summary: Our algorithm is efficient enough for moderate values of P, Q, and E. It's designed to solve the problem by determining if we can close all doors without causing an endless loop of doors opening and closing.

Conclusion - Farewell

As we wrap up our journey with Tarjan's algorithm, it's essential to remember its unique ability to find strongly connected components in directed graphs efficiently. Its depth-first search approach, combined with the use of low-link values, makes it an invaluable tool in a competitive programmer's toolkit. Whether you're tackling complex graph problems or exploring data structures, having Tarjan's algorithm under your belt can be a game-changer. I hope this was a good overview and the topics were well understood. Remember that there is a lot more to learn about graphs and we definitely didn't cover everything related to Tarjan's algorithm. Let me know your thoughts in the comment section below. Stay tuned for more and happy coding!